The Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg, Russia, was, from 1732 to 1917, the official residence of the Russian monarchs.

At this time: Museum. Opened for tourists.

Situated between the Palace Embankment and the Palace Square, adjacent to the site of Peter the Great’s original Winter Palace, the present and fourth Winter Palace was built and altered almost continuously between the late 1730s and 1837, when it was severely damaged by fire and immediately rebuilt. The alleged storming of the palace in 1917 as depicted in Soviet paintings and Eisenstein’s 1927 film “October” became an iconic symbol of the Russian Revolution.

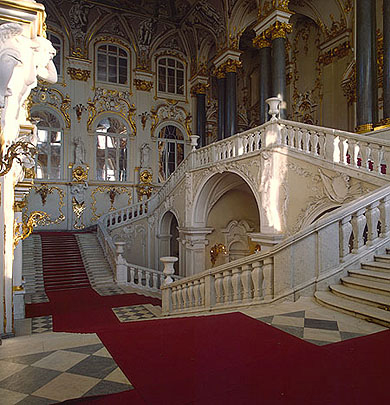

The palace was constructed on a monumental scale that was intended to reflect the might and power of Imperial Russia. From the palace, the Tsar ruled over 22,400,000 square kilometres (8,600,000 sq mi) (almost 1/6 of the Earth’s landmass) and over 125 million subjects by the end of the 19th century. It was designed by many architects, most notably Bartolomeo Rastrelli, in what came to be known as the Elizabethan Baroque style. The green-and-white palace has the shape of an elongated rectangle, and its principal façade is 250 m long and 100 ft (30 m) high. The Winter Palace has been calculated to contain 1,786 doors, 1,945 windows, 1,500 rooms and 117 staircases. The rebuilding of 1837 left the exterior unchanged, but large parts of the interior were redesigned in a variety of tastes and styles, leading the palace to be described as a “19th-century palace inspired by a model in Rococo style.

In 1905, the Bloody Sunday massacre occurred when demonstrators marched toward the Winter Palace, but by this time the Imperial Family had chosen to live in the more secure and secluded Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, and returned to the Winter Palace only for the most formal and rarest state occasions. Following the February Revolution of 1917, the palace was for a short time the seat of the Russian Provisional Government, led by Alexander Kerensky. Later that same year, the palace was stormed by a detachment of Red Army soldiers and sailors—a defining moment in the birth of the Soviet state. On a less glorious note, the month-long looting of the palace’s wine cellars during this troubled period led to what has been described as “the greatest hangover in history”. Today, the restored palace forms part of the complex of buildings housing the Hermitage Museum.

As completed, the overriding exterior form of the Winter Palace’s architecture, with its decoration in the form of statuary and opulent stucco work on the pediments above façades and windows, is Baroque. The exterior has remained as finished during the reign of Tsaritsa Elizabeth. The principal façades, those facing the Palace Square and the Neva river, have always been accessible and visible to the public. Only the lateral façades are hidden behind granite walls, concealing a garden created during the reign of Nicholas II. The hot building was conceived as a town palace, rather than a private palace within a park, such as that of the French kings at Versailles.

On 30 October 1917, the palace was declared to be part of the Hermitage public museums. This first exhibition to be held in the Winter Palace concerned the history of the revolution, and the public were able to view the private rooms of the Imperial Family. This must have been an interesting experience for the viewing public, for while Soviet authorities denied looting and damage to the palace during the Storming, eyewitness accounts describe the private apartments as the most badly damaged areas. The contents of the state rooms had been sent to Moscow for safety when the hospital was established, and the Hermitage Museum itself had not been damaged during the revolution.

Following the Revolution, there was a policy of removing all Imperial emblems from the palace, including those on the stonework, plaster-work and iron work. During the Soviet era, many of the palace’s remaining treasures were dispersed around the museums and galleries of the Soviet Union. Some were sold for hard currency while others were given away to visiting dignitaries. As the original contents disappeared and other items from sequestered collections began to be displayed in the palace, the distinctions between the rooms’ original and later use have become blurred. While some rooms have retained their original names, and some even the trappings of Imperial Russia, such as the furnishings of the Small and Large Throne Rooms, many other rooms are known by the names of their new contents, such as The Room of German Art.

Following the 1941–1943 Siege of Leningrad, when the palace was damaged, a restoration policy was enacted, which has fully restored the palace. Furthermore, as the Russian Government does not categorically shun remnants of the Imperial Era as was the case during Soviet rule, the palace has since had the emblems of the Romanovs restored. The gilded and crowned double headed eagles once more adorn the walls, balconies and gates. The Winter Palace is no longer the hub of a great empire, and the Romanovs no longer reside there, but the crowned Russian eagle serves as a reminder of the palace’s Imperial history.

Today, as part one of the world’s most famous museums, the palace attracts an annual 3.5 million visitors

Around this famous building, the Imperial Palace, there are many legends. Most of them narrates about walking the corridors and halls of the Palace of the ghosts of his former home of the kings and the people from their immediate surroundings. In the 19th century in the Winter Palace often “met” ghosts of Nicholas I and Alexander II and in the 20th century, the main character of the Hermitage legends has become Nicholas II, the Ghost of which, according to stories of the Museum workers, at least once appeared almost in all the rooms, although most often he was allegedly seen in a long dark corridors and the rooms are not intended for excursions, as well as in the larder.

Recently Ghost story was continued: in the Winter Palace was installed a new alarm system, which in the first months of work several times has been triggered. Started to spread rumors that if the reason for this was the ghosts. Then, however, all has stopped, apparently, ghosts how to bypass the alarm party.

Another group of legends ascribed to the Winter Palace various secret doors opened and underground passages, which, if you believe the rumors, you can walk to some of the other old buildings of Saint-Petersburg or even go beyond the city limits. The most popular is the myth that the Winter Palace is connected under the ground with the former mansion of Matilda Kshesinskaya, which had been at one time affair with his brother Nicholas II. And the disciples of Choir school in the Chapel are still trying to find the underground passage connecting the Winter Palace with the building of their school. However, the success of these searches so far failed.

Coat-of-arms hall.

Each room of the Suite became another link in the complex picture of characters, glorifying the native land. Armorial hall of the Winter Palace, intended for official ceremonies, was created Ð’.П.СтаÑовым at the end of the 1830s in the style of late Russian classicism. Images of coats of arms of the Russian provinces placed on the gilded bronze chandeliers. Entrances to the room фланкируют sculptural groups of old Russian warriors. The slender colonnade supporting the balcony with the balustrade, the frieze decorated with the ornaments of акантовых leaves, and the combination of gold with the white colour to create the impression of grandeur and solemnity.

The military gallery of 1812

The war gallery of 1812 – the most famous of the memorial rooms of the Palace – was built by the project of the outstanding architect of Russian classicism Rossi’s designs (1775/77-1849) and inaugurated on December 25 1826года, the anniversary of the expulsion of Napoleon’s army from Russia. Here placed 332 portraits of the generals of the Russian army, participants of the war of 1812 and the foreign campaign of 1813 – 1814 years. In the Gallery are submitted by places for 13 portraits of the victims, the image of which has not been found. The portraits were commissioned by Alexander I the artist George Dawe. Meeting between the Russian Emperor and the fashion of the English portrait painter took place in the German city of Aachen, where in the fall of 1818, hosted the first Congress of the Holy Alliance of the countries – winners of the Napoleon army.

In the back of the room on the end wall is located gala portrait of Emperor Alexander I (performed by Franz Kruger). Next represented by parade portraits of the monarchs of the allied States – Prussia and Austria. Portraits of field Marshal Ðœ.И.Кутузова and Ðœ.Б.Ð‘Ð°Ñ€ÐºÐ»Ð°Ñ de Tolly are located on the sides of the door leading to the St George hall (Large throne) hall.

During the fire of 1837 all the portraits were rescued and returned to its proper place in the restored Ð’.П.СтаÑовым hall.

Malachite living room.

The malachite room of the Winter Palace, created by the architect Ð.П.Брюлловым in the late 1830-ies., served as the front drawing-room of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Nicholas I. the Finishing of the hall is unique: the columns, pilasters, the details of the fireplaces and decorative vases are decorated with malachite in the technique of «Russian mosaic». Especially elegant form of the interior gives the combination of bright green of the stone, with abundant gilding and saturated crimson tone draperies. One of the walls is decorated with allegorical figures symbolizing the Day, the Night and the Poetry of the brush Ð.Виги. The large malachite vase standing under the shadow of, and furniture made П.ГамбÑом the drawings of the О.де de Montferrand were saved during the fire of 1837. They were part of the decoration of which was located in this place before the fire Яшмовой reception.

In malakhitovaya the living room from June to October of 1917 took place the session of the Provisional government.

The white hall.

The white hall was created Ð.П.Брюлловым for the wedding of the future Emperor Alexander II in 1841. This entirely in shades of white interior is rich plastic decoration: stucco ornaments cover cons and pilasters, the tape of the frieze is decorated with figures of the cherubs, integrated games. In the Central part of the hall, over the images of armor, placed bas-relief figures of ancient Roman gods; the columns with magnificent Corinthian capitals are topped with figures personifying the arts. In the interior harmoniously look picturesque panels of the French landscape painter of the 18th century. Г.Робера. In the hall of the exposition furniture Д.Рентгена, the famous masters of the age of classicism.

During the reign of Emperor Alexander II, the hall had its own purpose: then held festive receptions, were not carried out in the Northern part of the Palace, as under Nicholas I, and in the southern section, where were located private rooms of the Emperor and the Empress.

The old photo. Taken November 7, 1917 near the Winter Palace.

It was this turbulent period of Russian history, known as the February Revolution, which for a brief time saw the Winter Palace re-established as a seat of government and focal point of the former Russian Empire. In February 1917, the Russian Provisional Government, led by Alexander Kerensky, based itself in the north west corner of the palace with the Malachite Room being the chief council chamber. Most of the state rooms were, however, still occupied by the military hospital.

It was to be a short occupation of both palace and power. By 25 October 1917, the Provisional Government was failing and, realising the palace was a target for the more militant Bolsheviks, ordered its defence. All military personnel in the city pledged support to the Bolsheviks, who accused Kerensky’s Government of wishing to “surrender Petrograd to the Germans so as to enable them to exterminate the revolutionary garrison.